Article: Art 101 | Why Do Artists Continue to Make Abstract Art?

Art 101 | Why Do Artists Continue to Make Abstract Art?

What is abstract art?

Abstract art, at its core, is a visual language that moves beyond direct representation to explore form, color, gesture, and material in ways that evoke rather than depict. It seeks to express what lies beneath or beyond the surface of reality—emotions, perceptions, symbols, systems—making space for ambiguity, intuition, and interpretation.

Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art

While often associated with 20th-century Western modernism, abstraction has long existed across global cultures, from Islamic geometric designs to Andean textiles and Indigenous American sand paintings, where stylized or non-representational forms conveyed cosmological, spiritual, and cultural meaning. In the Western canon, abstraction evolved through key modern and postmodern movements, each probing different aspects of art’s potential to convey meaning without mimetic imagery.

Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art

This overview focuses on abstraction through six interrelated genres that illustrate the richness and range of the form: Abstract Expressionism, which channels emotion and psyche through gesture and color; Geometric Abstraction, which explores form, structure, and visual clarity; Mystical Abstraction, which taps into spiritual and symbolic dimensions; Abstract Photography, which challenges representational norms through the lens; Mixed Media Abstraction, which blends materials, techniques, and conceptual strategies; and Light & Space Abstraction, which engages perception and environment as medium. Each reflects distinct ways artists have used abstraction to question, express, and expand how we see and perceive the world.

Abstract Art Through Time

Abstract art is often associated with the postmodern movements of the 20th century, with artists such as Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Rothko commonly regarded as pioneers. However, abstraction has long predated the Western canon. In many pre-modern Indigenous American traditions, abstraction is evident in woven textiles, ceramics, and sand paintings—forms rich in symbolic patterns that reflect cosmology, seasonal cycles, and identity. Pre-Modern African art used stylized forms in sculpture and ritual objects to convey ancestral knowledge, while Islamic art developed intricate geometric systems rooted in divine order. These traditions used abstraction not as a break from representation but as a means to preserve meaning. While modern abstraction reshaped Western ideas of art, non-representational forms as vessels of spiritual and cultural knowledge have a much older, global lineage.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of John Molloy Gallery

This investigation focuses on modern and postmodern abstraction when the Western art world saw radical shifts in form, technique, and concept. By narrowing the scope, we can trace how abstraction evolved in response to changing cultural, social, and technological forces—and how artists redefined what art could be in ways that still resonate today.

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism began in New York in the 1940s and ’50s, marking an important shift in Western art. It was the first American movement to gain international attention, moving the center of the art world from Paris to New York after World War II. Although influenced by European modernism, it was shaped by the unique tensions and anxieties of postwar America. Inspired by Surrealism’s focus on the unconscious and existentialism’s search for meaning, Abstract Expressionists used abstraction to express deep emotion and universal truths. Their canvases became spaces for action—large, expressive works where gesture, spontaneity, and inner experience came together. For many, Abstract Expressionism still defines what abstract art looks like: huge fields of color, bold brushstrokes, and a powerful drive to find meaning through paint.

Among the most influential figures in Abstract Expressionism were Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler—artists who radically redefined what painting could express. Pollock’s drip technique made the act of painting itself central to the work, while de Kooning’s volatile canvases merged abstraction and figuration. Rothko and Newman turned to vast fields of color and minimalist forms to evoke spiritual and metaphysical experiences. Krasner and Mitchell expanded the movement’s emotional and formal language through complex, energetic compositions rooted in memory and landscape. Frankenthaler’s soak-stain method introduced a new kind of lyricism and fluidity, bridging the gestural abstraction of Abstract Expressionism and the Color Field painting movement. Together, these artists placed emotion, spontaneity, and inner life at the heart of modern art, laying the groundwork for much of contemporary abstraction.

Photo credit Gordan Parks, for Life Magazine

Within the movement, two overlapping approaches emerged: Gestural Abstraction and Color Field painting. Gestural abstraction, seen in the work of Pollock, de Kooning, and Mitchell, emphasized the physical act of painting—brushstrokes, drips, and smears recorded the artist’s body and psyche in motion. These works feel immediate and dynamic, often turbulent. In contrast, Rothko, Newman, and Frankenthaler pursued a quieter mode through Color Field painting, using expansive areas of color to invite reflection and emotional stillness. While gestural works channeled energy and action, Color Field compositions offered atmosphere and transcendence. Both approaches sought to access the sublime and the internal, marking a turn in modernism away from representation and toward direct experience.

Geometric Abstraction

Geometric abstraction is a style of abstract art that emphasizes the use of simple geometric forms—lines, shapes, and color fields—to explore space, rhythm, and perception without direct reference to the natural world. Drawing its roots from early 20th-century movements like Constructivism and the Bauhaus, geometric abstraction prioritizes structure over the aesthetic of spontaneity, offering a visual language that is both precise and expansive. Artists working in this tradition often strive to distill complex ideas into essential forms, creating compositions that are both formal and philosophical.

Pioneers such as László Moholy-Nagy brought a radical vision to geometric abstraction, fusing technology and art in pursuit of new ways of seeing. Ellsworth Kelly and Carmen Herrera each pushed the language of minimal color and shape into pure visual clarity—Kelly with his bold, unmodulated color fields and Herrera with her rigorously balanced, often hard-edged forms. Lydia Okumura disrupts the precision of geometry with interventions in space, making illusion and perspective integral to her wall-bound installations. Similarly, Esther Mahlangu draws on traditional Ndebele design to bring cultural and historical resonance to a geometric lexicon, merging ancestral patterns with contemporary abstraction. Together, these artists show the range and vitality of geometric abstraction as both a global and deeply individual practice.

Mystical Abstraction

Mystical Abstraction refers to a current within abstract art that seeks not only to depict the external world but to reveal the inner, the invisible, and the transcendent. Rooted in spiritual philosophies such as Theosophy, anthroposophy, and various Indigenous cosmologies, this form of abstraction uses color, geometry, and symbolism to access what lies beyond physical perception. Hilma af Klint, long overlooked in canonical art history, stands as a foundational figure in this tradition. Working in the early 20th century, she created large-scale, radically non-representational works guided by spiritual “higher beings” decades before. Bridging the pre-modern and modern periods, her practice merged 19th-century spiritualist traditions with a distinctly forward-looking visual language, positioning her as a precursor to abstraction itself.

Other artists deepened this trajectory: Swiss healer Emma Kunz produced intricate, mandala-like drawings that served both as artworks and instruments of healing, while American painter Agnes Pelton aligned her glowing compositions with transcendental meditation and the metaphysical symbolism of the American Southwest. Emily Kame Kngwarreye, an Anmatyerre elder from Australia’s Utopia region, transformed traditional Aboriginal art into a dynamic form of spiritual abstraction. Beginning her career late in life, she translated decades of ceremonial knowledge into vivid canvases marked by shimmering dots, gestural marks, and vibrant stripes that pulse with the rhythms of her desert homeland, Alhalkere. Her paintings compress vast cosmological narratives into seemingly abstract forms—embodying ancestral law, kinship, and sacred Dreaming sites—while forging a bridge between Indigenous storytelling and global abstraction. Wassily Kandinsky, whose 1912 treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art remains a touchstone, advocated for abstract form as a means to access higher spiritual realities. Georgia O’Keeffe’s luminous interpretations of the natural world similarly blur the line between the physical and the ineffable, offering a visual vocabulary for the sublime.

In more recent years, the tradition of mystical abstraction has continued across cultures and continents. From artists drawing on esoteric knowledge systems to those working within Indigenous frameworks of cosmology and place, abstraction remains a potent vehicle for spiritual inquiry. Whether evoking the unseen architecture of the universe or the charged energies of a sacred site, mystical abstraction persists as a living lineage—one that seeks not only to depict reality but to transform perception itself.

Abstract Photography

Abstract photography, as explored by pioneers such as Barbara Morgan, Florence Henri, and Aaron Siskind, emerged alongside and often in dialogue with the more well-known tradition of abstract painting that developed in the early to mid-20th century. While painters such as Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Pollock pushed abstraction to dissolve recognizable forms into pure color, line, and gesture, these photographers similarly sought to move beyond literal representation—but through the lens of the camera. Barbara Morgan’s fluid images of dancers from the 1930s and ’40s echo the rhythmic dynamism found in Abstract Expressionism, capturing movement as a kind of visual music. Florence Henri’s 1920s and ’30s photographic experiments with reflections and geometric distortions parallel the Cubist and Constructivist painters’ interest in breaking down form and space. Aaron Siskind's work aligns closely with Abstract Expressionism by focusing on textured surfaces that emphasize materiality and emotional intensity. Together, these artists' work locates abstract photography as a vital, parallel thread within the broader modernist movement in abstract art.

Collage and Found Image Abstraction

Mixed media abstraction often thrives on a spirit of playfulness and experimentation, as vividly exemplified by Henri Matisse’s late cutouts such as The Sheaf (La Gerbe) (1953). Matisse, confined by illness to working with scissors and colored paper, reinvented collage as a joyous act of creation. Matisse's cutouts blur the boundaries between drawing, painting, and collage, using bold shapes and vibrant colors to evoke a dynamic sense of rhythm and movement.

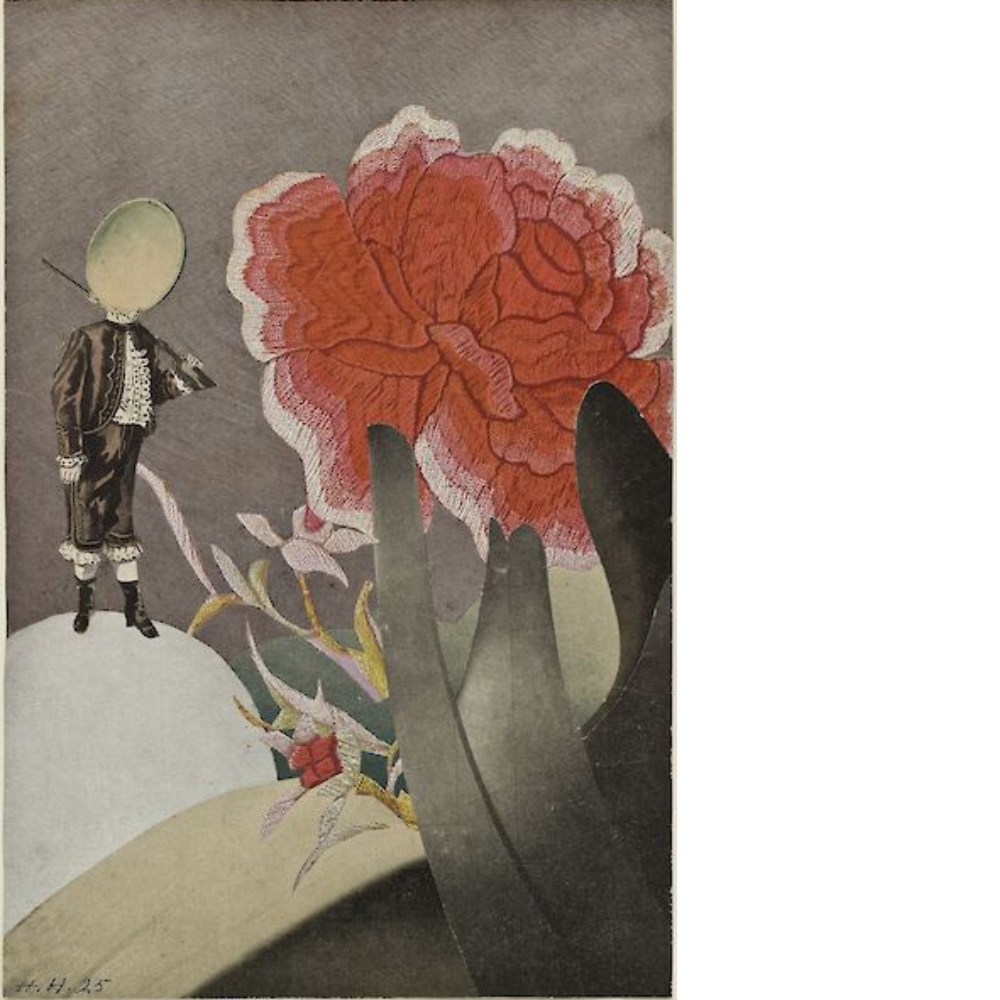

Höch’s approach is both playful and subversive, using collage as a sharp tool of cultural critique that exposes the contradictions of Weimar-era society. By cutting and reassembling images from mass media—particularly advertisements, fashion magazines, and political propaganda—she revealed the constructed nature of gender roles and the absurdity of dominant power structures. Her works challenge traditional representations of femininity, nationalism, and bourgeois values, often with biting irony. This blend of humor, critique, and aesthetic innovation positions Höch as a pioneer who expanded abstraction into a potent form of social and political commentary.

Photo Credit: MOMA

John Baldessari expanded the boundaries of abstraction by merging photography, painting, and conceptual strategies. Throughout his career, he questioned the conventions of visual language, often using found photographs, painted shapes, and text to disrupt narrative clarity and draw attention to the act of meaning-making itself. By doing so, Baldessari interrogates the function of images in contemporary culture and art history, destabilizing fixed interpretations. His playful yet cerebral manipulations of media question the authority of the photographic image and expand abstraction into a layered dialogue between visual language and conceptual thought. Together, these artists exemplify how mixed media abstraction can simultaneously celebrate formal innovation, cultural critique, and the fluidity of meaning.

Light and Space Abstraction

1960s and 1970s as a distinct movement centered on the viewer’s sensory experience of light, color, and space. Departing from traditional reliance on physical form or representational imagery, these artists used light as a primary medium—sculpting environments that shifted perception and heightened awareness of spatial presence. Artists like James Turrell craft immersive installations that use natural and artificial light to reshape our perception of space, blurring the line between environment, light, and viewer. Olafur Eliasson expands this approach by integrating natural phenomena, such as water, fog, and climate, with engineered light environments, crafting multisensory, interactive installations that deepen engagement with perception and the environment.

Photo courtesy James Turrell Studio. © James Turrell

Helen Pashgian and Ann Veronica Janssens also explore the subtleties of light and atmosphere within this tradition. Pashgian’s works often involve smooth, translucent forms that seem to glow from within, emphasizing the materiality of light and its interplay with space. Janssens employs fog, haze, and minimal interventions to subtly alter spatial perception and evoke a sense of disorientation or wonder. Light and Space abstraction closely relates to Minimalism and Conceptual Art in its reduction of art to elemental phenomena and its focus on the viewer's experience over objecthood. It intersects with Op Art’s focus on optical effects and Kinetic Art’s engagement with movement and perception. This influence extends into contemporary installation, environmental, and digital art, where artists continue to explore sensory experience, phenomenology, and the shifting boundaries between viewer, artwork, and space.

Why Are Artists Still Making Abstract Art?

Artists continue to create abstract art because abstraction remains a powerful visual language for what cannot be easily named: the internal, the immaterial, the spiritual, the emotional, and the speculative. Abstraction is not a style frozen in mid-century modernism but a living, evolving practice—a way of engaging with the world that allows artists to render memory, cosmology, sensation, and place without the constraints of figuration. In a time when the visible world is saturated with images, abstraction carves out space for the unseen.

Tappan Artists Working with Abstraction

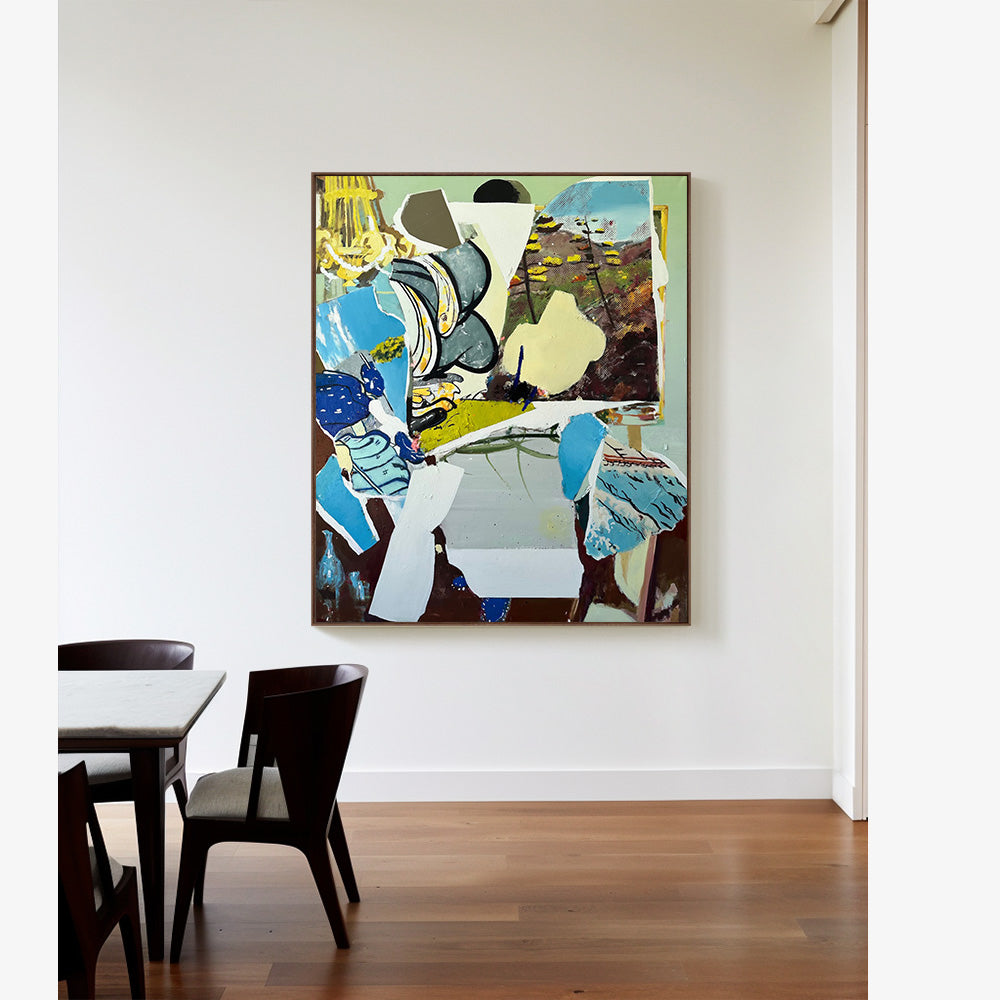

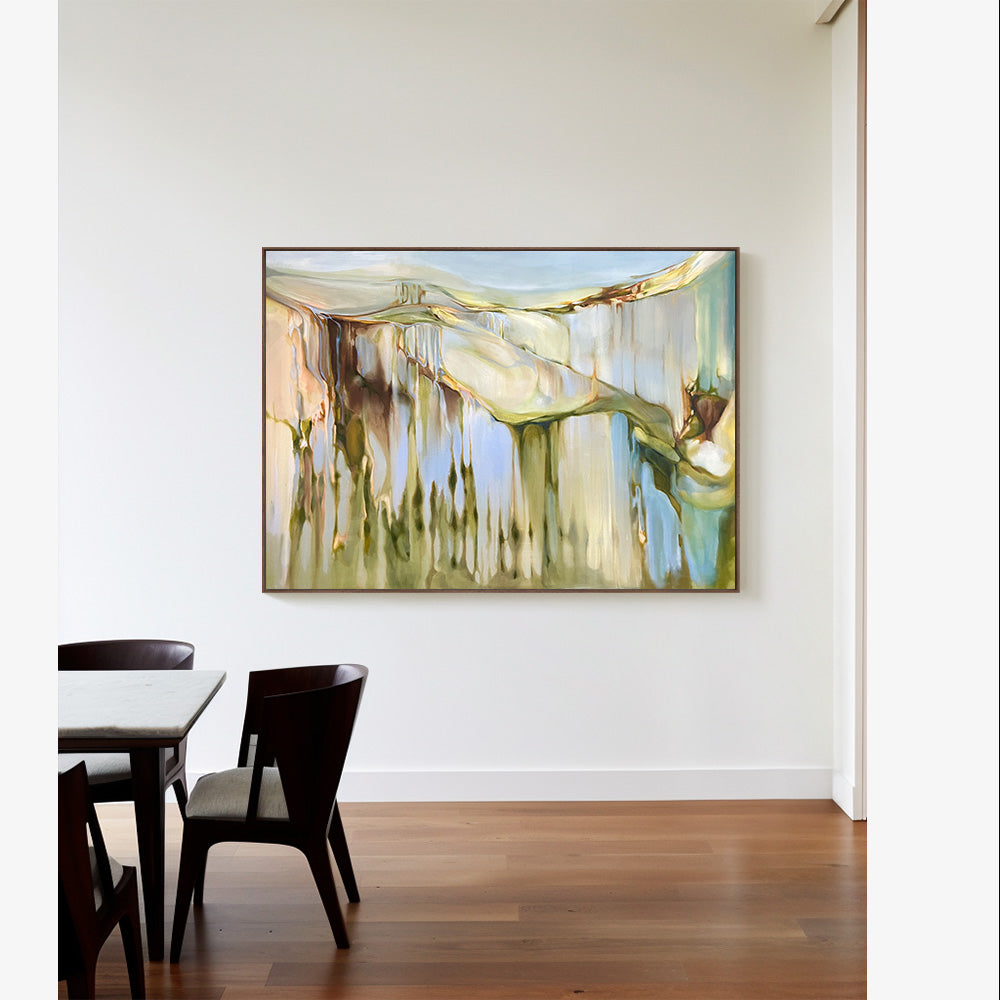

Michael Harnish

Michael Harnish’s abstracted landscapes evolve the visual language pioneered by fellow Southern Californian John Baldessari, particularly in their shared use of photographic sources to create images that transcend mere documentation. While Baldessari famously challenged the boundaries of image and text—using found photographs to question perception, authorship, and context—Harnish applies a similar strategy to landscape painting, transforming photographic material into richly layered compositions. Rather than faithfully depicting nature, his works become perceptual collages, where terrain is entangled with memory, culture, and lived experience.

In Harnish’s paintings, the landscape is not a neutral surface but one shaped by aesthetic tradition, collective memory, and physical place. His work evokes the visual and psychic clutter of Southern California—a region defined as much by cinematic mythologies and cultural sprawl as by natural beauty. Architectural fragments, signage, and atmospheric effects merge with painterly gestures to reflect the tension between presence and disappearance, belonging and estrangement. His landscapes resonate with postmodern image-making, where authorship is diffuse, and the terrain becomes a palimpsest of visual history and cultural debris. Positioned alongside Baldessari, David Hockney, and Vija Celmins, Harnish pushes further into abstraction, revealing how landscapes are not only inhabited but remembered, projected onto, and remade.

Michael DeSutter and Leigh Wells

Michael DeSutter and Leigh Wells both harness collage as a vibrant medium to explore abstraction through color theory and found imagery, particularly from magazines. DeSutter’s practice often involves layering fragments of printed material and carefully selecting hues and shapes to create rhythmic, dynamic compositions that evoke movement and depth. His intuitive use of color contrasts and harmonies transforms everyday images into abstract visual dialogues. Similarly, Leigh Wells mines magazine pages to extract fragments of color and form, recombining them into carefully balanced abstractions that highlight the emotional resonance of color relationships. Both artists use collage not simply as assemblage but as a way to investigate how color and composition interact to generate meaning beyond representation. Their work foregrounds the tension between the familiar and the abstract, inviting viewers to reconsider how fragmented imagery can coalesce into new visual languages. By recontextualizing found images through the lens of color theory, DeSutter and Wells push collage beyond its decorative or narrative function into a realm of formal and conceptual inquiry.

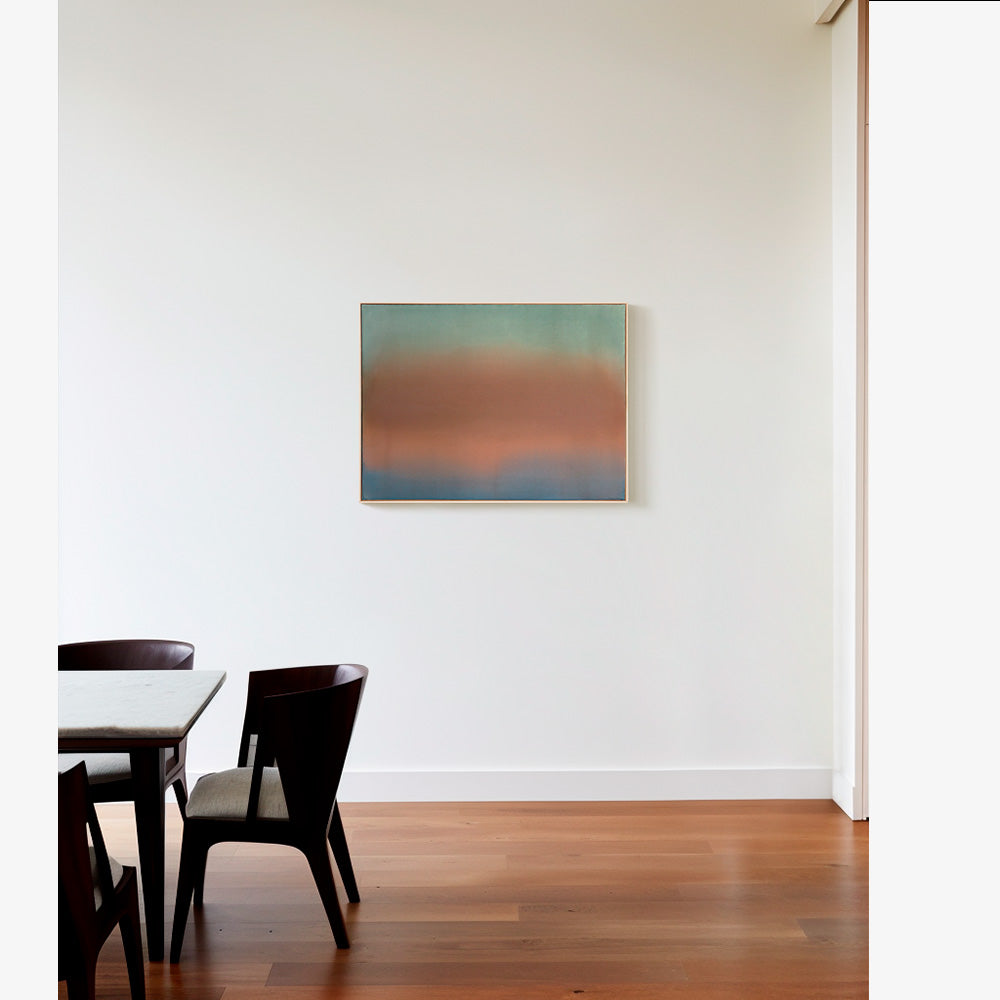

Ali Enache

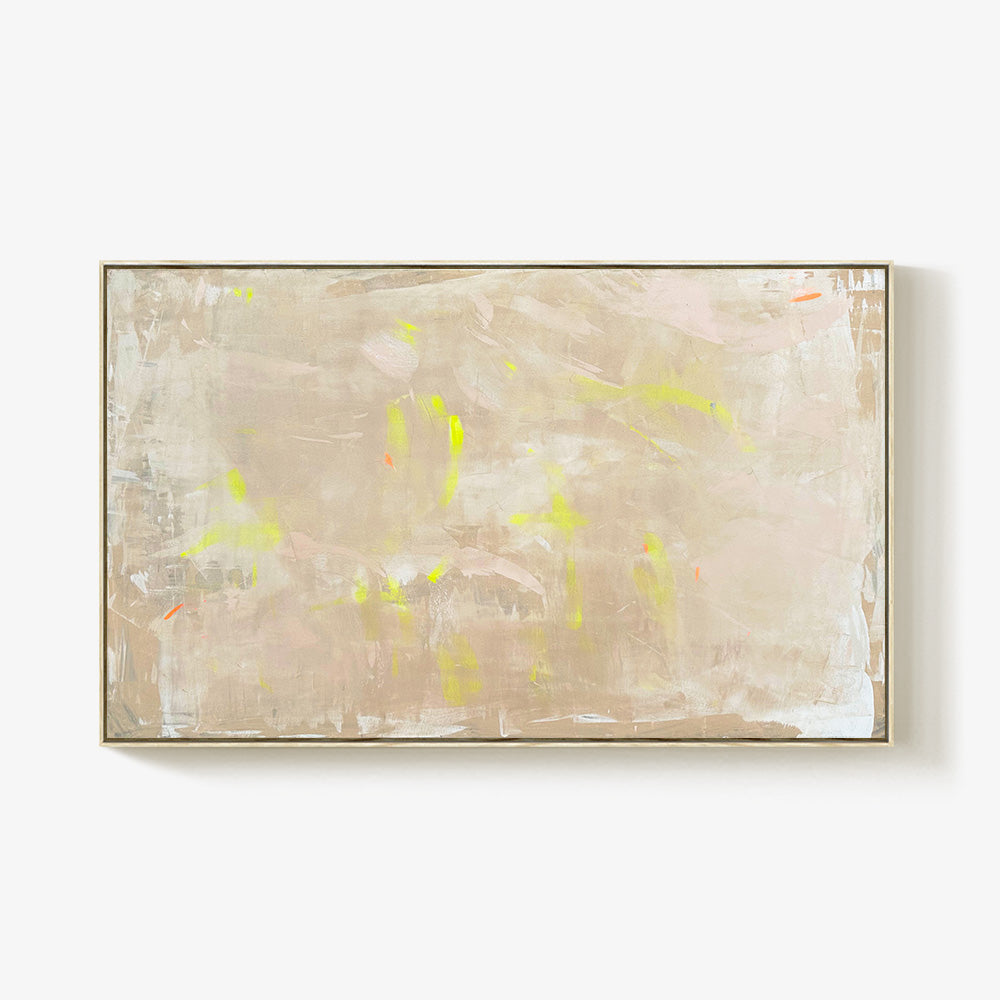

Ali Enache’s work draws deeply from the Color Field tradition, using expansive swaths of color to create immersive experiences that heighten perceptual awareness. Her paintings explore the nuanced relationships between hue and saturation, inviting quiet contemplation of color as both a sensory and emotional presence. Through subtle gradations and luminous layers, her compositions radiate an inner glow that dissolves the boundary between surface and space, creating a sense of depth and atmosphere that transcends the flatness of the canvas.

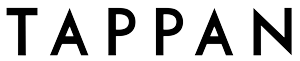

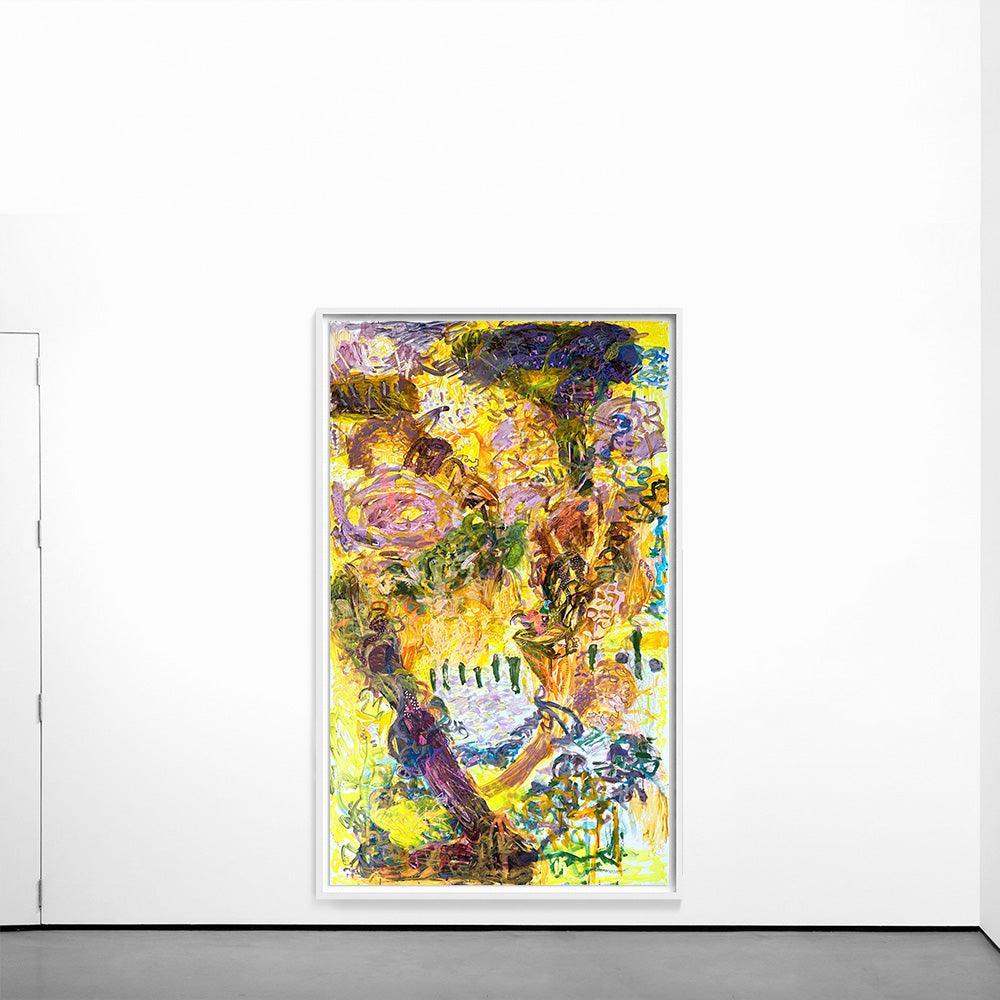

Ali Beletic

Ali Beletic expands gestural abstraction through spontaneous, expressive mark-making that captures the immediacy of emotion and movement. Her brushstrokes serve as direct traces of presence and intention, transforming painting into a space of personal expression and psychological depth.

Astri Styrkestad Haukaas

Astri Styrkestad Haukaas’s abstraction is rooted in nature and poetic experience, translating moments of awe and transcendence into visual form. Through subtle shifts in color and texture, her work evokes the rhythms and moods of the natural world, offering a quiet, reflective space where paint becomes a language of emotional and sensory resonance.

Fei Li

Fei Li’s abstract gestures draw from two distinct sources of inspiration. Some works honor the unseen labor involved in domestic work, while others are inspired by poetry that reflects on everyday life and emotion. Her marks, which reference labor, evoke the rhythms and motions of daily tasks, transforming gestural abstraction into a subtle tribute to often-overlooked or undervalued work. Separately, her poetry-inspired pieces deepen the emotional and contemplative qualities of her practice. This dual approach situates her abstraction within both socio-political and personal realms, using the language of gesture to make the invisible visible and profoundly felt.

Luis Ignacio Figallo

Luis Ignacio Figallo masterfully blends the visual language of painting with fluid, gestural shapes to create three-dimensional hanging sculptures. His works capture the unhurried, effortless gesture of painting, translating it into a sculptural form that seems to float and flow in space. This sense of fluidity creates a compelling tension against the rough, unyielding surfaces of hand-carved reclaimed wood, which grounds the pieces with a tactile, earthy presence. The contrast between the graceful curves and the raw materiality highlights the dynamic interplay between movement and solidity, as well as softness and strength.

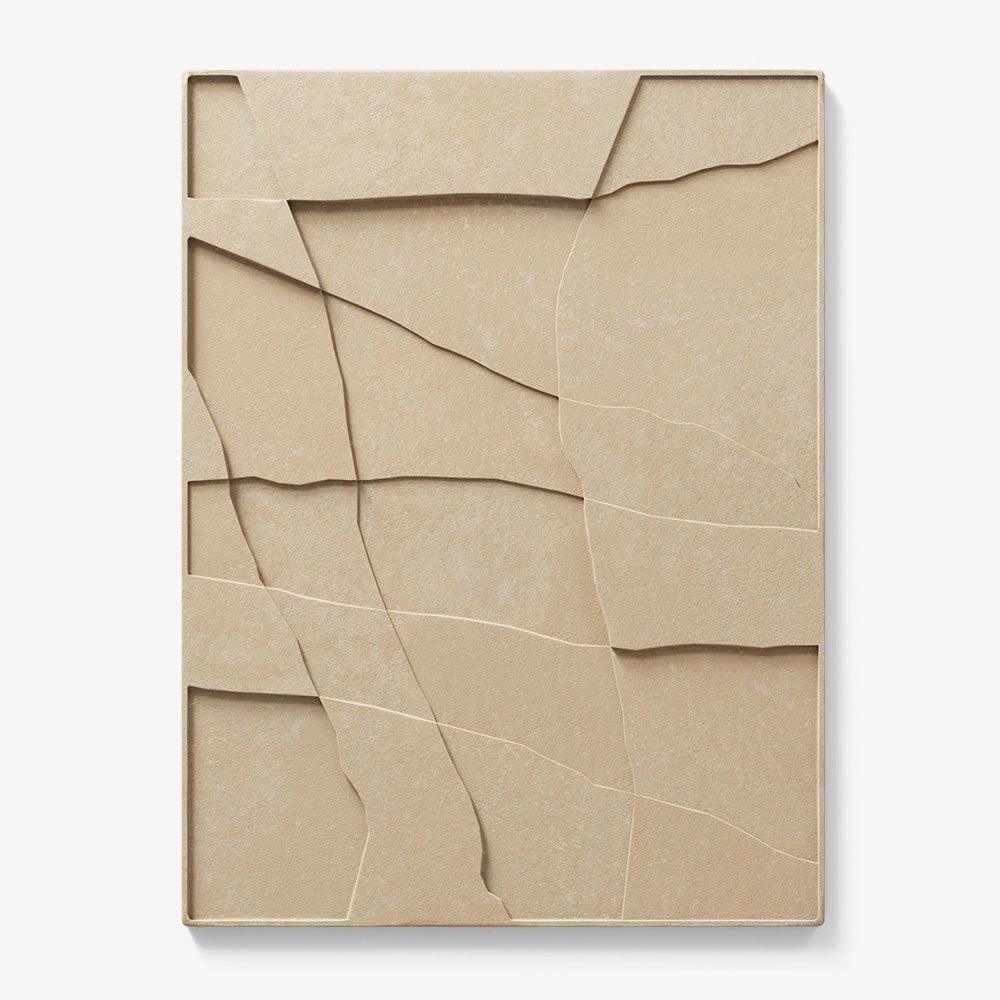

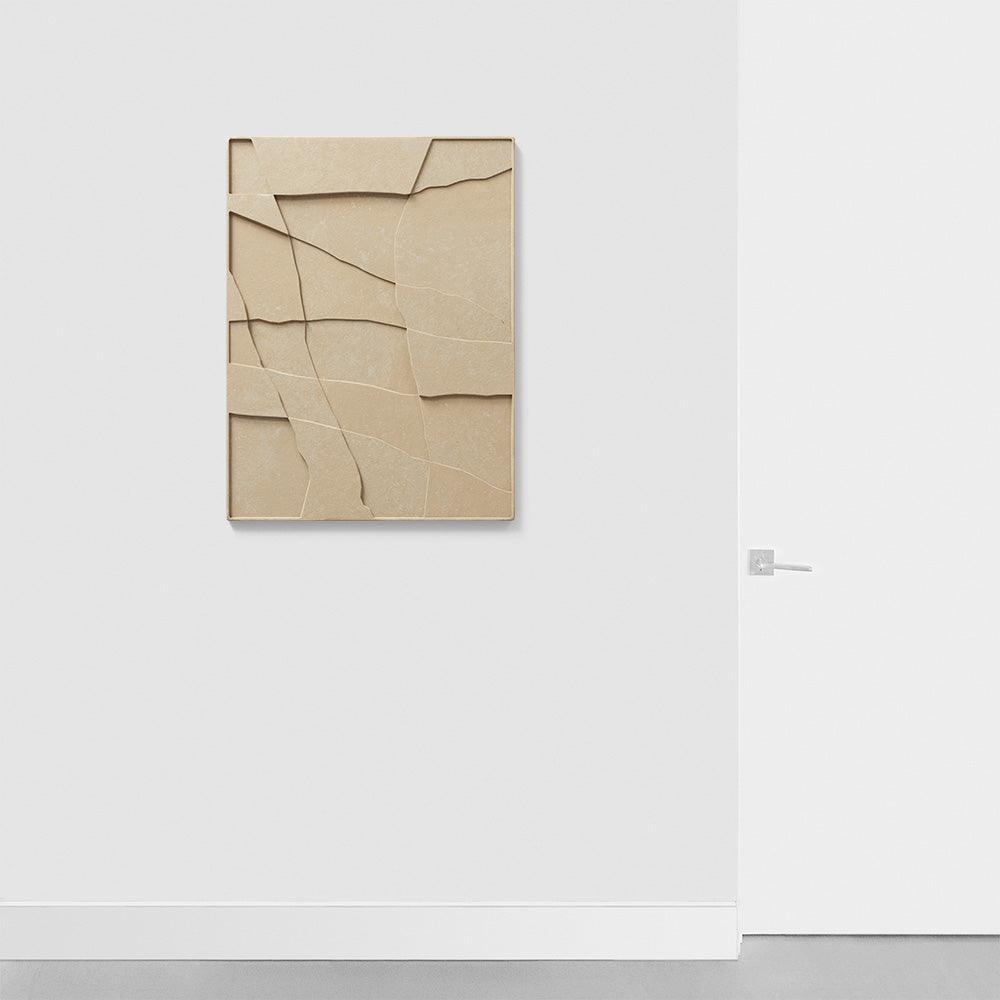

Colt Seager and Sara Marlowe Hall

Colt Seager and Sara Marlowe Hall craft richly textured, layered abstract works that explore the language of geometry while embracing the beauty of expressive irregularity. Their compositions often hinge on geometric forms, but rather than rigid precision, they allow edges to breathe and flow, creating space for gesture to emerge. This interplay between structured shapes and spontaneous marks reveals an organic tension where the mathematical meets the expressive. The artists celebrate the expressive irregularity of the line as a site of vitality and human touch, inviting viewers to appreciate the nuances that arise when form loosens, and gestures take hold.

Viktor Kobylianski

In Viktor Kobylianski’s atmospheric paintings, the materiality of the work itself becomes a central focus, blurring the boundary between nature and industry. Through the use of unconventional media, Kobylianski builds surfaces that feel tactile and worn, capturing the textured reality of city life.

Brian Merriam

Within the lens of abstract photography, Brian Merriam’s series Inner Weather and Reverse Plasma both exemplify his interest in using the photograph not as a final document, but as a starting point for transformation. In both bodies of work, Merriam moves beyond static representation to explore how place can serve as a mirror for inner states and perceptual shifts.

In Inner Weather, Merriam photographs natural landscapes through the petals of flowers, using their translucent hues to tint each scene. This technique explores the idea of “seeing the environment through the prism of itself”, with each image becoming a meditation on how nature shapes and reflects emotional states. The result is a series of atmospheric works that blur the boundary between external landscape and inner experience. In Reverse Plasma, Merriam manipulates photographs of the northern lights, inverting their spectral brilliance so that patches of brightness become areas of shadow. This reversal unsettles the expected visual narrative, transforming celestial phenomena into quiet, abstract meditations. Across both series, Merriam reimagines photography as a tool for introspection and metaphor, using light, color, and atmosphere to render states of mind as much as scenes of the natural world.

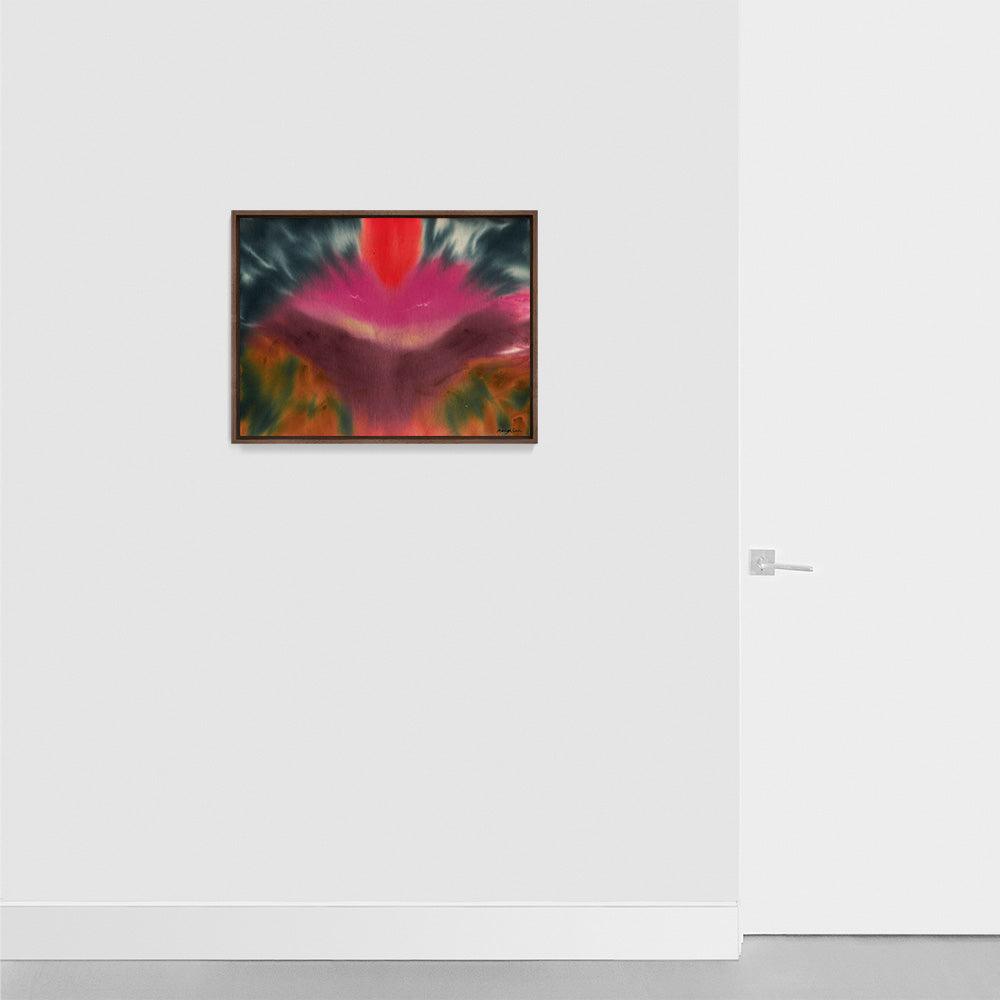

AOTH

AOTH’s dreamy, intuitive brushwork exemplifies a key aspect of abstract art: the emphasis on emotion and gesture over representation. Her fluid strokes dissolve concrete forms into atmospheric fields of color, inviting viewers to engage with the painting on a sensory and emotional level. This approach aligns with the broader abstract tradition that values spontaneity and the expressive potential of paint as a means to evoke mood and inner experience beyond literal depiction.

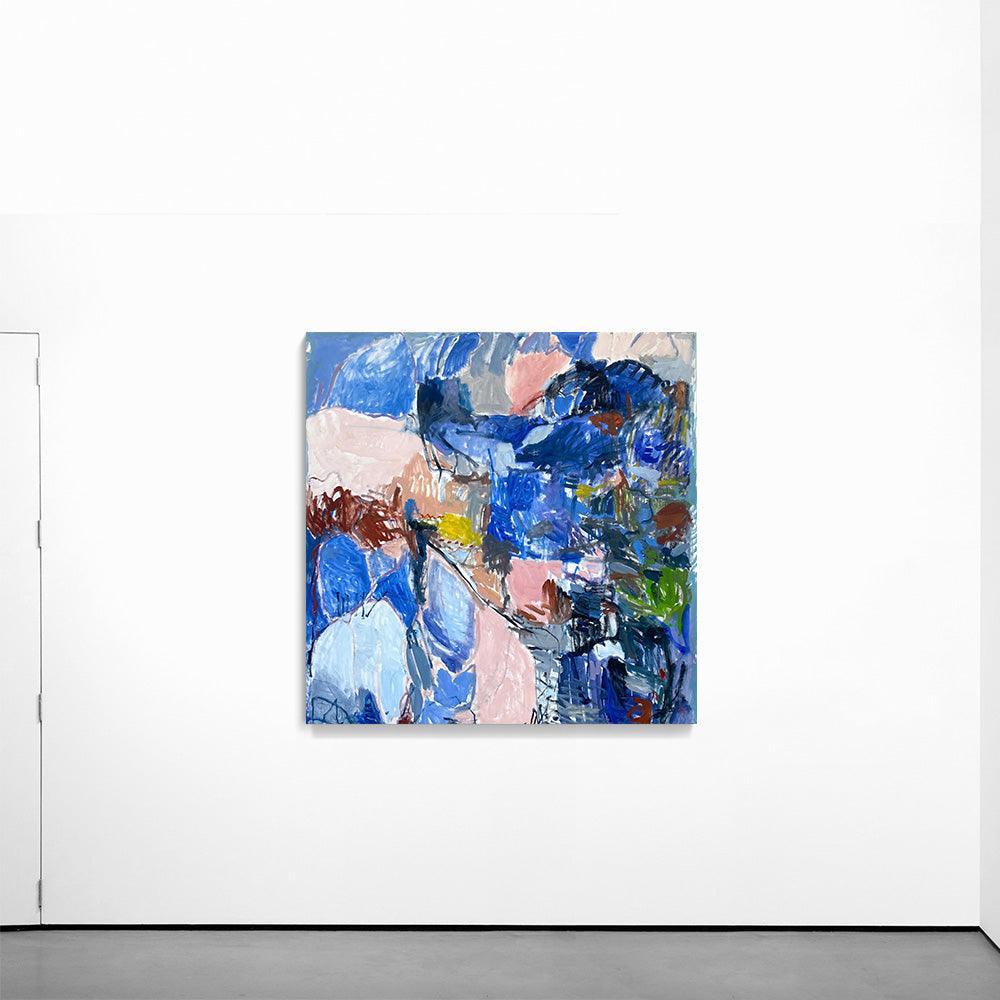

Marleigh Culver

Marleigh Culver’s work explores abstraction through both painting and printmaking, drawing on the lineage of modernists such as Helen Frankenthaler and Henri Matisse. Her paintings channel the lush, immersive quality of Frankenthaler’s stained canvases, using saturated color and fluid gestures to create emotionally charged fields. In contrast, her limited edition prints evoke the playful clarity of Matisse’s cutouts, abstracting organic shapes into crisp, graphic forms. Whether through paint or print, Culver’s compositions strip nature down to its essentials—revealing how form, color, and rhythm can speak beyond representation.

Neil Kryszak

Neil Kryszak’s photography expands the possibilities of abstract art by using the camera not to document but to explore the perceptual and material qualities of light itself. In his work, light becomes both subject and medium—moving through glass, bending across surfaces, and interacting with the camera's motion to produce compositions that are as much about sensation as they are about form. These luminous, color-saturated images align with traditions in abstract photography, where perception, movement, and material interaction take precedence over representation. Kryszak’s practice underscores how abstraction continues to evolve through contemporary technologies and intuitive experimentation.

OVSKA

Ovska’s collages and prints draw deeply from the legacy of geometric abstraction, channeling the pioneering spirit of Kazimir Malevich. By employing sharp shapes, bold lines, and dynamic compositions, OVSKA revisits Malevich’s radical reduction of form to its purest geometric essence. Her work reinterprets these early 20th-century principles through contemporary materials and layered collage techniques, creating a dialogue between flatness and depth, as well as order and fragmentation.

Loralee Jade

Loralee Jade’s work recalls the fluidity and organic forms found in both Morris Louis’s paintings and Georgia O’Keeffe’s abstract works. Through her use of pouring techniques, she creates delicate, translucent washes of color that flow and shift across the surface. Like Louis and O’Keeffe, Jade blends the natural movement of pigment with a considered approach to color and form, creating compositions that balance spontaneity with intentionality.

The Heidies

The photographic duo The Heidies share a keen interest in capturing the effects of dance and gesture that is deeply reminiscent of Barbara Morgan’s pioneering work. Much like Morgan, who famously documented the dynamic movements of modern dancers with a focus on rhythm, form, and energy, The Heidies explore how the body in motion can be translated into still images that convey both physicality and emotion. Their photography emphasizes the interplay between light, shadow, and movement, freezing fleeting gestures that reveal the grace and power of dance

Petra Schott

Petra Schott’s gestural abstraction builds on and expands the Abstract Expressionist tradition by continually exploring the dynamic interplay of mark and color. Her work pushes beyond conventional boundaries, using bold, expressive gestures and vibrant hues to create compositions that are both emotionally charged and visually complex.

Satsuki Shibuya

Satsuki Shibuya’s abstract practice draws from the lineage of lyrical abstraction, infusing the tradition with influences from music and poetry. By pairing visual work with bilingual poetry, Shibuya expands abstraction beyond form and gesture into a multi-sensory language of emotion and reflection.