Art 101 | Figurative Art: Origins, Evolution, and Enduring Importance

Figurative art, defined broadly as any art that represents real-world subjects, is one of the oldest and most resilient forms of artistic expression. In the context of the Western Hemisphere, figurative art has played a foundational role in the visual culture of both ancient civilizations and modern societies. Unlike abstraction, which seeks to strip down or depart from visible reality, figurative art engages with it—sometimes faithfully, other times interpretively. It includes depictions of animals, landscapes, and the human figure. From prehistoric cave paintings in the Americas to contemporary silhouettes and portraits, figurative art in the West has remained a central mode through which artists explore identity, nature, culture, and the human condition. While it has evolved significantly over time, its continued relevance can be seen through the works of both historical and contemporary figures such as Pablo Picasso, David Hockney, Jenny Saville, and Kara Walker.

Origins and Early Development

The origins of figurative art date back to the Paleolithic era, with cave paintings in Lascaux and Altamira depicting animals in motion and human figures engaged in ritual or survival. These early images were not merely decorative; they had symbolic and spiritual functions, potentially used to convey stories, record events, or summon forces beyond human control. In this sense, figuration served as one of humanity's earliest forms of communication—a bridge between lived experience and mythic imagination.

In ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece, figurative art took on new functions. Egyptian tomb paintings, for instance, depicted the human body in rigid, idealized forms meant to signify social status and divine order. Greek artists gradually moved toward more naturalistic representation, culminating in classical sculpture that celebrated human anatomy, movement, and ideal proportion. These works laid the foundation for much of Western art’s enduring emphasis on the body as a vessel of meaning, beauty, and philosophical inquiry.

The Renaissance and the Golden Age of Figuration

The Renaissance (14th–17th century) marks a high point in the history of figurative art. With renewed interest in Greco-Roman ideals and scientific observation, artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael produced works that combined anatomical precision with emotional depth. The invention of linear perspective, along with advancements in oil painting, allowed for increasingly lifelike depictions of space and volume. Figures appeared embedded in real environments, with expressions and gestures conveying individual psychology and narrative tension.

This period also saw a widening of subjects—beyond religious themes, artists depicted mythological scenes, portraits, and eventually, secular daily life. The human figure became not only an emblem of divine grace but also a reflection of worldly knowledge, humanism, and individuality. Portraiture in particular became a key vehicle for asserting identity, status, and personality—an approach that persists to this day.

Baroque to Modernity: Emotion, Realism, and Disruption

In the Baroque period (17th century), figurative art turned more theatrical and emotionally charged. Artists like Caravaggio used dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro) and intense naturalism to make figures feel immediate and alive, often highlighting moments of spiritual ecstasy, martyrdom, or internal conflict. Meanwhile, Dutch painters like Rembrandt and Vermeer brought unprecedented attention to the intimacy of domestic life and inner states of mind.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of Romanticism and Realism—movements that broadened figuration's scope. Romantic artists like Francisco Goya and Eugène Delacroix depicted dramatic, often disturbing scenes that reflected psychological and political upheaval. Realists like Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet turned their attention to contemporary society, painting workers, urban life, and moments previously deemed unworthy of high art. Their insistence on representing the world “as it is” helped bridge the gap between figuration and social critique.

At the dawn of the 20th century, figurative art underwent profound transformations in response to photography, industrialization, and the trauma of modern warfare. The camera freed painters from the need to replicate visible reality, allowing them to experiment with form, perspective, and symbolism. Movements such as Expressionism, Surrealism, and Fauvism used the human figure as a conduit for inner states, dreams, and primal emotion. Artists like Egon Schiele, Käthe Kollwitz, and Francis Bacon contorted the body to express existential distress and psychological fragmentation.

Figurative Practices: Key Movements & Artists

The Renaissance and the Birth of the Western Figurative Tradition

The Western tradition of figurative painting finds its roots in the Renaissance, when artists began to merge observational study with classical ideals of proportion and beauty. Masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael approached the human body not only as a subject of visual interest but as a vessel of intellect, divinity, and emotion. Their work was shaped by an intense engagement with anatomy, perspective, and the rediscovered principles of Greco-Roman art. This period laid the conceptual and technical foundations for centuries of academic training, influencing the evolution of both Classical Realism and Academic Painting.

Classical Realism and Academic Painting

This style emphasizes anatomical accuracy, ideal proportion, and balanced composition, rooted in Renaissance and Greco-Roman traditions. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Ingres set the foundation for centuries of academic training and representation.

Romanticism and Expressionism

Romanticism highlights emotion, drama, and individual experience through dynamic brushwork and intense color. Expressionists like Edvard Munch distorted the human figure to convey psychological and emotional tension.

Jenny Saville and the Reclamation of the Body

Jenny Saville, a key figure in contemporary figurative painting, focuses intensely on the human form—often rendered at a monumental scale and in unflinching detail. Her subjects are usually female, painted with a raw, corporeal presence that rejects classical ideals of beauty. Works like Propped (1992) and Fulcrum (1999) depict flesh in motion and tension, revealing the body as a lived, dynamic site of experience.

Saville’s gestural brushwork and layered paint surface recall both Renaissance anatomical studies and Abstract Expressionist energy. Her work resists objectification, instead positioning the human figure—particularly the female body—as complex, powerful, and self-determined. In doing so, she extends the tradition of figurative painting into the realm of feminist critique and contemporary identity politics.

Surrealism and Symbolic Figuration

Surrealist artists such as Salvador Dalí and Frida Kahlo used realistic imagery to explore dreams, the unconscious, and symbolic meaning. The human figure appears in strange or metaphoric scenarios that challenge logic and reality.

Salvador Dali

Salvador Dalí was a leading figure in the Surrealist movement, known for his dreamlike, often bizarre imagery and meticulous painting technique. He used the human figure in psychologically charged, symbolic compositions—bending reality to explore themes of time, desire, decay, and the subconscious. Works like The Persistence of Memory (1931) show his ability to render fantastical scenes with almost photographic precision.

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

Impressionists like Degas and Renoir painted figures in everyday settings with loose brushwork and changing light. Post-Impressionists like Cézanne and van Gogh pushed figuration toward abstraction and emotional resonance.

Modernist and Cubist Figuration

Cubists like Picasso fragmented and reassembled the figure into geometric forms, redefining spatial and bodily perception. Modernist figuration often emphasized experimentation over realism, integrating influences from global art traditions.

Pablo Picasso and the Fragmentation of the Figure

In the 20th century, Pablo Picasso revolutionized figurative art by reimagining the human form through abstraction and fragmentation. While often associated with Cubism, Picasso never abandoned figuration. Instead, he challenged its conventions. His groundbreaking painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) presents five female figures in a radically abstracted and confrontational style, blending influences from African masks, Iberian sculpture, and modernist experimentation.

Picasso’s work demonstrated that figuration could be expressive, symbolic, and conceptual rather than merely representational. He helped move the focus from the appearance of the figure to its psychological, cultural, and formal implications. His work inspired a generation of artists to approach landscapes, still lifes, and portraits as spaces for experimentation, not just observation.

Social Realism and Narrative Figuration

Social Realists such as Diego Rivera used figuration to depict working-class life and political struggle with clarity and dignity. Narrative figuration expanded this approach with more aggressive or satirical portrayals of contemporary events.

Fernando Botero and the Politics of Exaggeration

Fernando Botero, one of Latin America's most celebrated artists, developed a uniquely recognizable style marked by exaggerated proportions and volumetric figures—often described as “inflated” or “fat.” Through paintings and sculptures of people, animals, and still lifes, Botero created a visual language that is simultaneously humorous, critical, and deeply rooted in the traditions of figurative art. His subjects—ranging from bullfighters and nuns to political leaders and ordinary citizens—are rendered with monumental presence and uncanny softness.

While at first glance his work may seem lighthearted or decorative, Botero’s use of distortion serves a deeper purpose. His 2005 Abu Ghraib series, for example, depicted prisoners abused by U.S. forces during the Iraq War using his signature rotund style, intensifying the horror by contrasting visual whimsy with moral outrage. Similarly, his frequent depictions of Colombian life often reflect the excesses of power, violence, and religious authority. Botero’s figures are rarely just formal studies—they are critiques of colonialism, capitalism, and corruption masked in aesthetic exaggeration.

Photorealism and Hyperrealism

Photorealists like David Hockney recreated images with photographic precision to question perception and mechanical reproduction. Hyperrealism exaggerates fine detail to emphasize surface, texture, and the uncanny nature of realism.

David Hockney and the Reaffirmation of the Personal

While Picasso fragmented the figure, David Hockney brought it back into focus—alongside the spaces it inhabits. Emerging in the 1960s, Hockney’s work often depicts real-world subjects like landscapes, domestic interiors, swimming pools, and, centrally, people. His stylized, colorful scenes of Southern California, such as A Bigger Splash (1967), balance formal clarity with emotional nuance. These sun-drenched compositions blur the line between realism and dream, offering a modern reinterpretation of traditional figurative genres.

Hockney’s portraiture, particularly his double portraits, reflects a deep interest in interpersonal relationships and psychological space. Whether painting friends, lovers, or family, he uses gesture, gaze, and setting to convey emotional resonance. His later forays into landscape—especially his vivid depictions of the Yorkshire countryside—demonstrate that figuration can encompass not only the human body but also the environments we live in and move through.

Contemporary Figurative Styles

Today’s artists blend cultural references, politics, and media influences to explore identity, race, gender, and memory through figuration. Artists like Kara Walker use the body as a site of critique, power, and presence.

Kara Walker and the Power of Historical Figuration

Kara Walker brings a distinctly conceptual and historical approach to figurative art. Best known for her black paper silhouettes, Walker uses simplified but evocative forms to explore themes of race, gender, power, and historical trauma—particularly in the context of American slavery and its enduring legacies. Her figures, though rendered without facial detail, are immediately recognizable as human and often caught in tense, emotionally charged scenes.

In works such as Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994), Walker deploys antebellum aesthetics to subvert romanticized images of the American South. Her stark silhouettes recall the decorative arts but turn them into tools for critique. Through figurative storytelling, she exposes the violence and contradictions of American history, using the body—often fragmented, violated, or performative—as a site of reckoning.

Cut paper on wall. 69 x 80 in.

Figurative Artists with Tappan

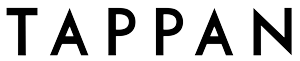

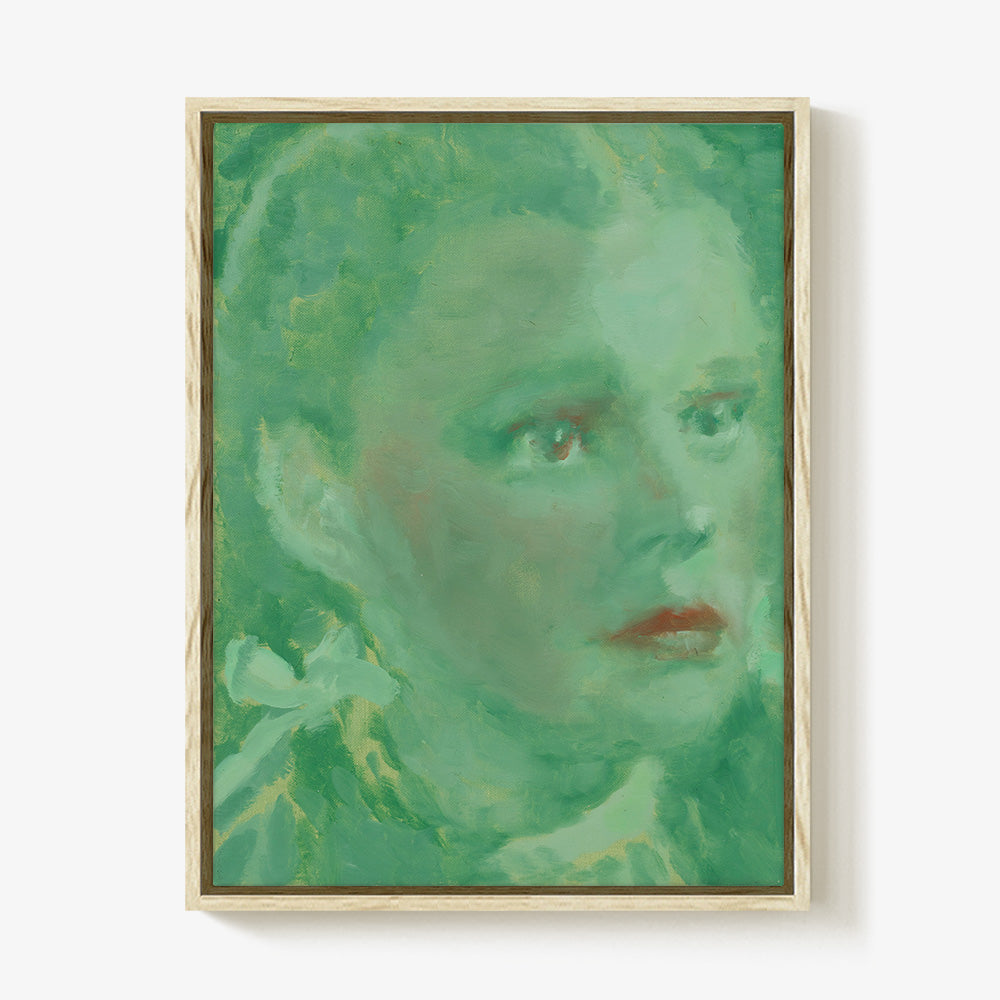

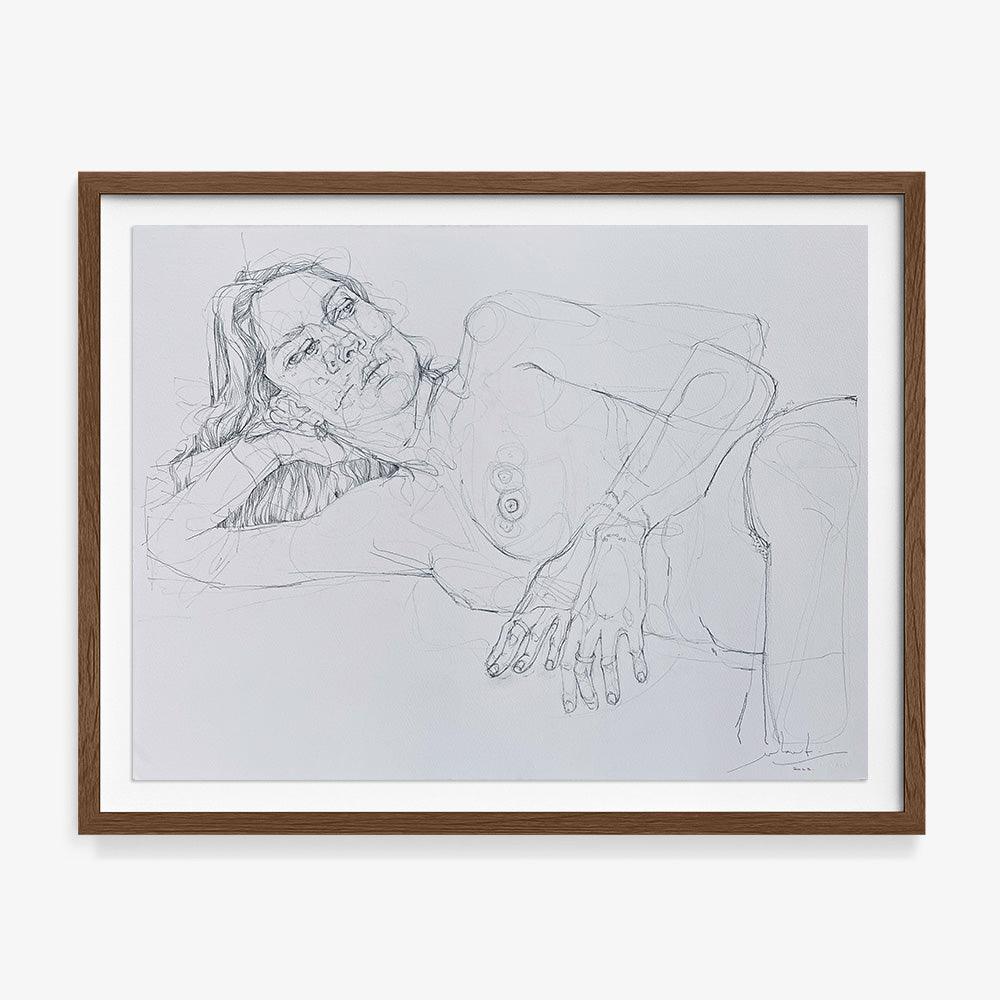

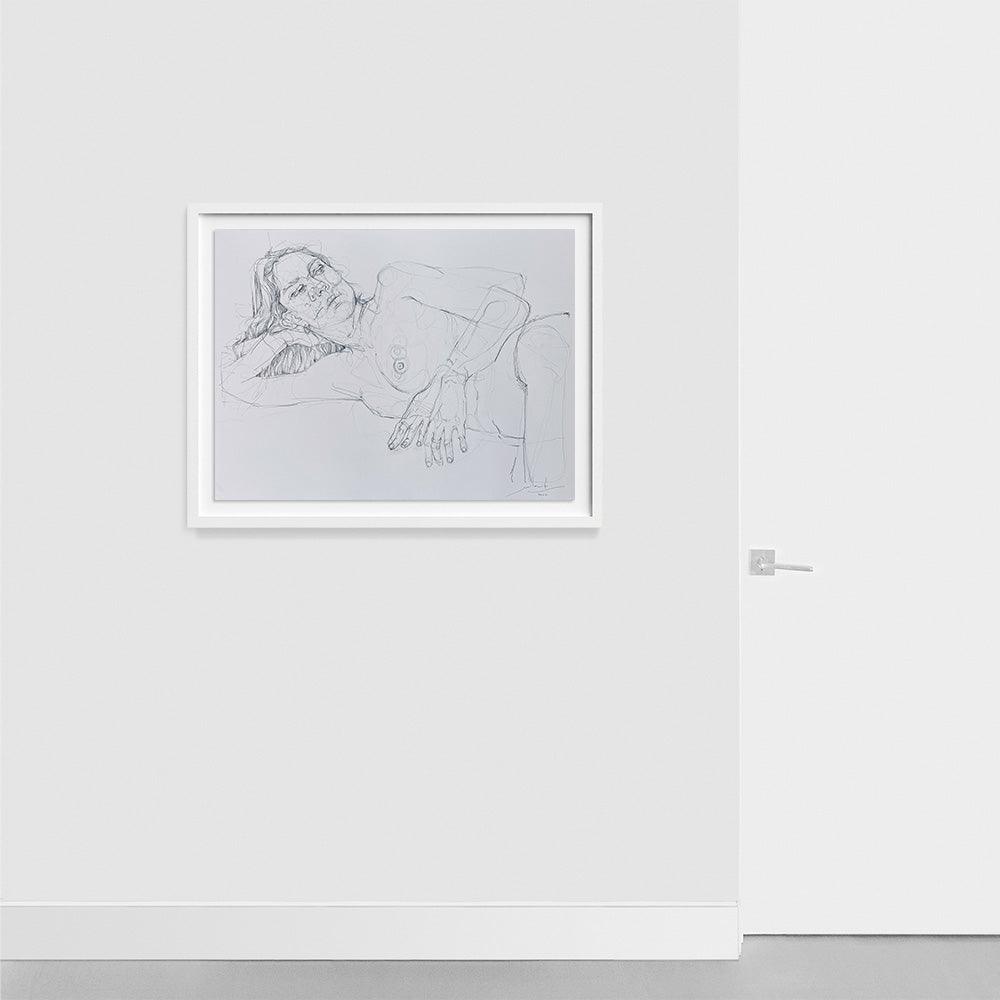

Anatole Heger

Anatole Heger’s figurative practice centers on the human form as a site of emotional and psychological intensity. His work often blurs the boundary between representation and abstraction, using distortion, fragmentation, and layered textures to evoke vulnerability and transformation. Through painting and drawing, Heger explores the tension between physical presence and inner experience, creating figures that feel both intimate and elusive.

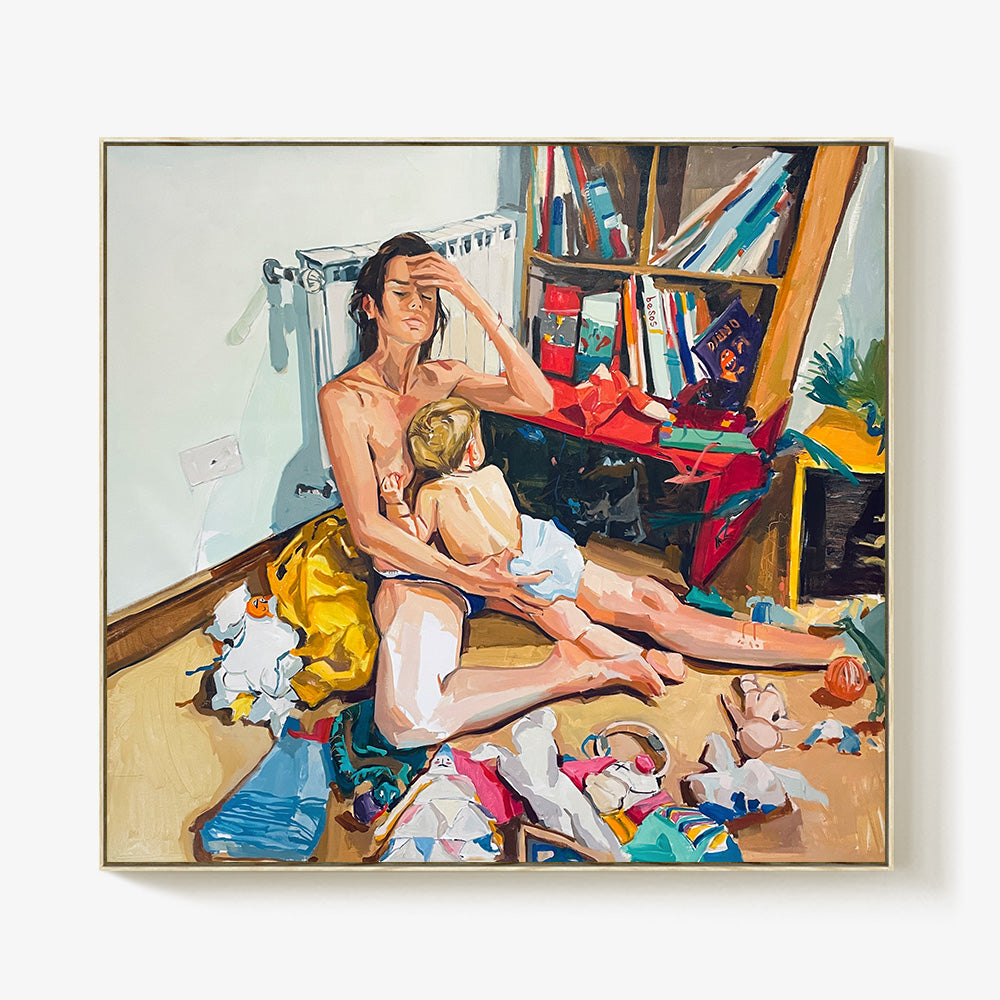

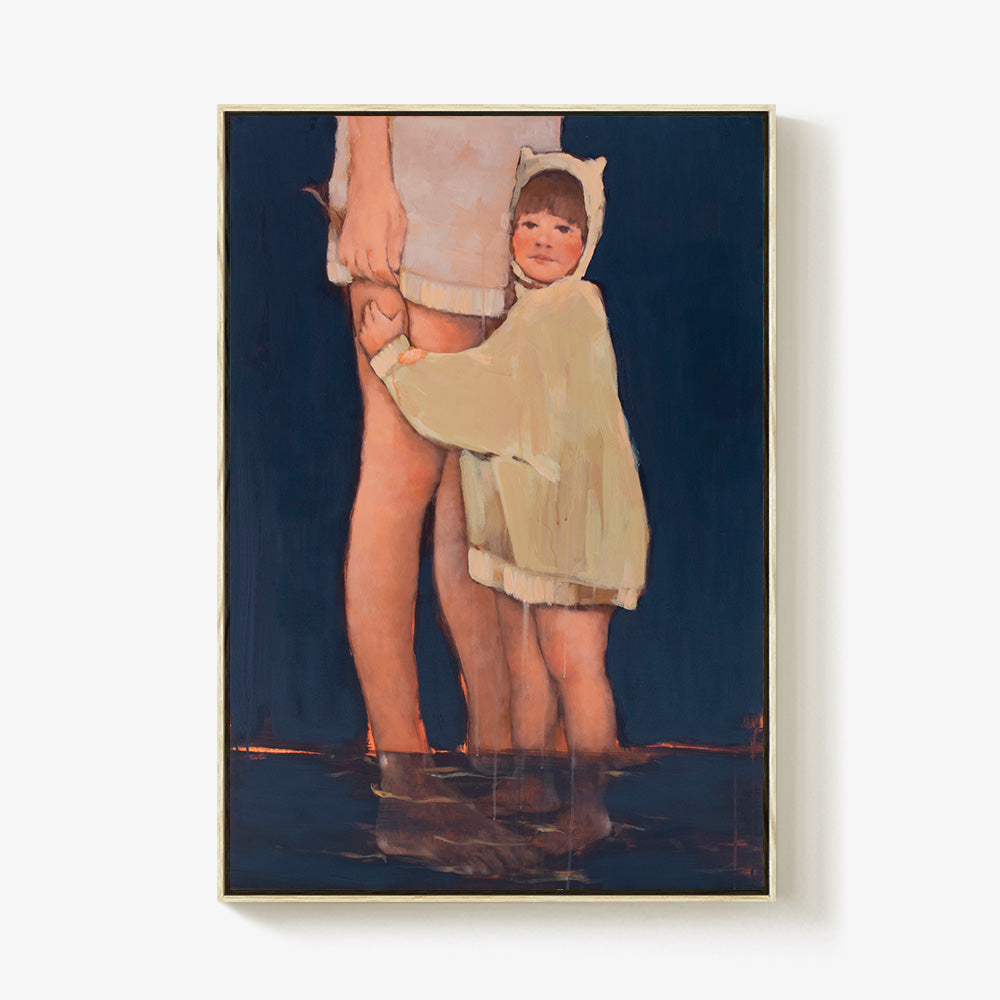

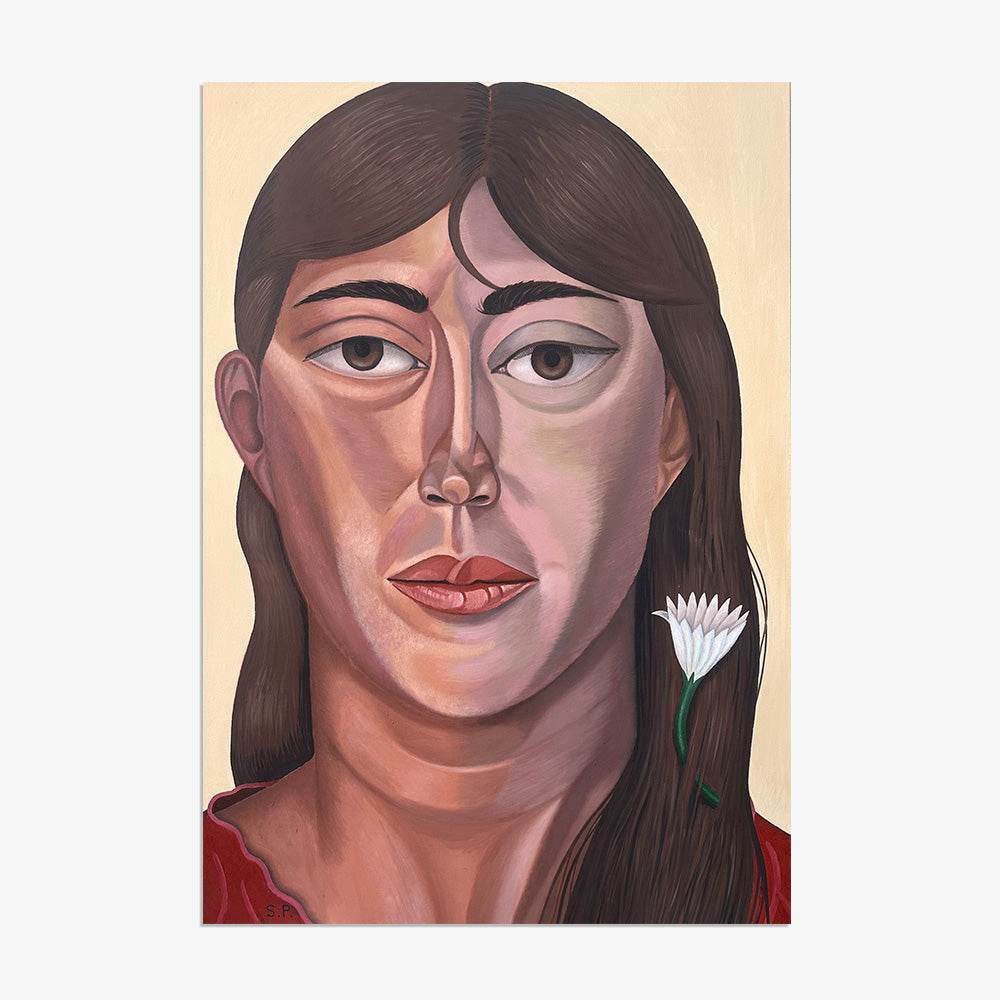

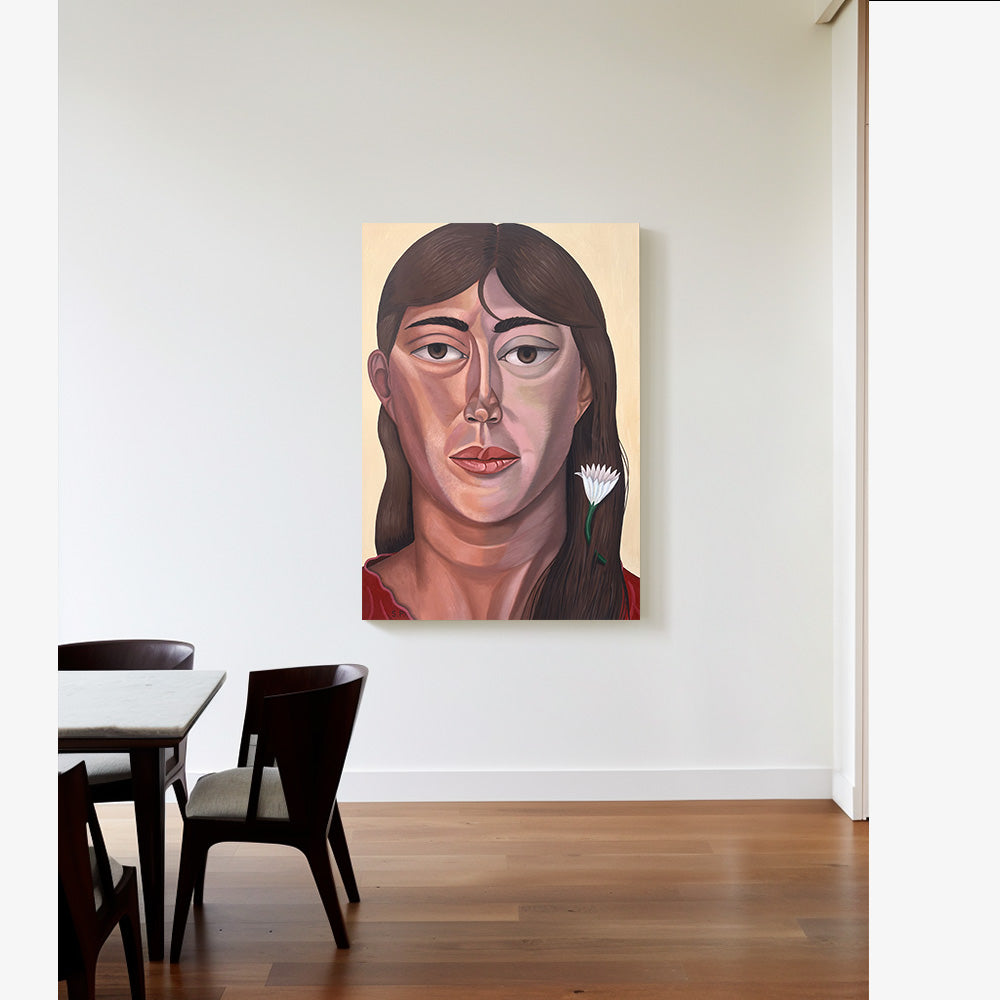

Irinka Talakhadze

Irinka Talakhadze’s figurative paintings depict the human form in states that feel both fleeting and dreamlike, hovering between perception and imagination. Using layered materials like acrylic, chalk, and pastel, she emphasizes transparency and spontaneity to evoke psychological depth and emotional nuance. Influenced by surrealist and modernist traditions, her work explores the tension between reality and illusion, often reflecting on themes of identity, memory, and inner transformation.

Aliya Abs

Aliya Abs’s figurative practice explores the quiet strength and emotional nuance of transformation, often through the lens of seasonality and the natural world. In her recent series, intimate portraits and floral still lifes unfold in a soft, romantic palette, where color becomes a vehicle for feeling. Repeated dotted patterns lend a playful rhythm to the work, echoing petals or breath—light, intuitive, and suggestive of innocence. Her portraits, painted with calm precision, embody the emotional undercurrents of renewal, offering figures that feel both grounded and gently evolving. Through tenderness and restraint, Abs captures a world in bloom, where beauty is not decoration but quiet resolve.

Conclusion: The Persistent Power of Real-World Subjects

Figurative art has endured for tens of thousands of years because it speaks to our desire to understand the world around us and our place within it. Whether depicting landscapes, animals, or the human figure, figurative art grounds our visual experience in the tangible and familiar—even when filtered through radical stylistic innovations. From ancient cave walls to modern museums, it has served as a record of cultural values, personal narratives, and collective imagination.

Artists like Picasso, Hockney, Saville, and Walker have each transformed figurative art by pushing its boundaries and expanding its meanings. Their works show that representation is not a static practice, but a dynamic field in which artists continually reinterpret the real world in response to their time, their tools, and their truths. In today’s increasingly digital and disembodied world, the sustained relevance of figurative art lies in its ability to reassert the power of looking, feeling, and being—through bodies, through landscapes, and through images that continue to speak across centuries.